Ventral Slot Technique

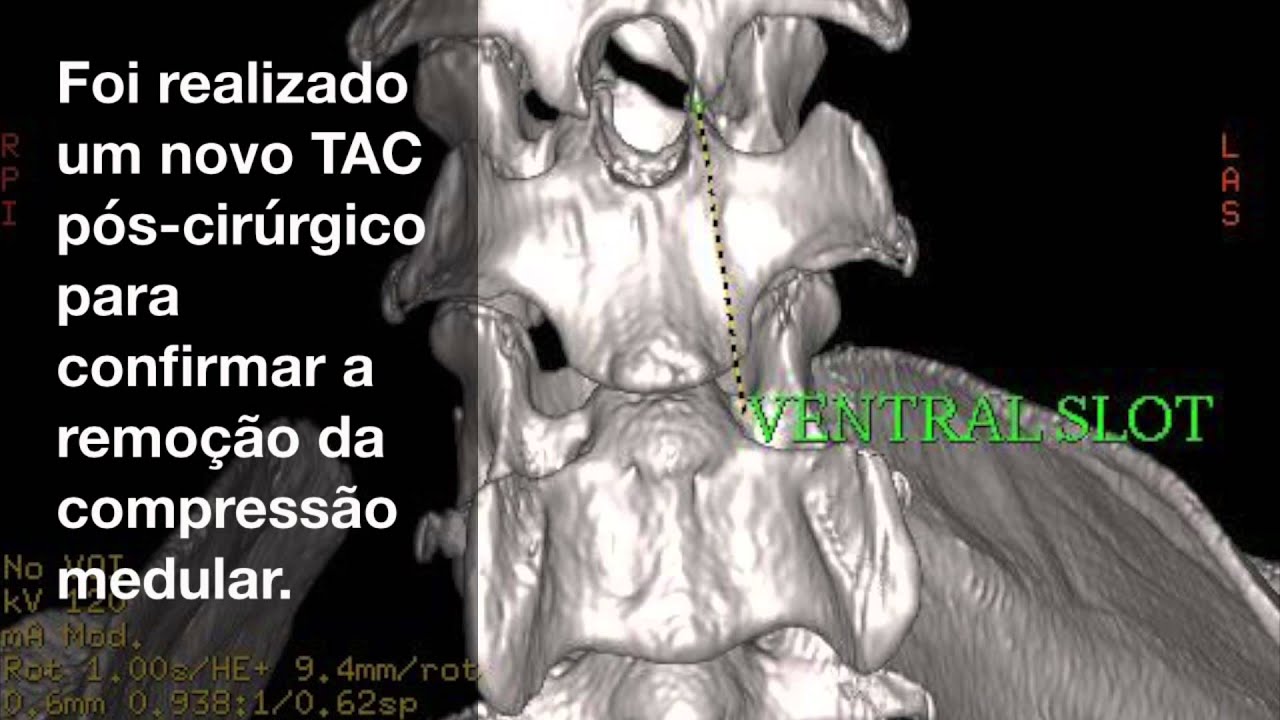

Posted : admin On 4/9/2022Ventral Slot This is the procedure employed when a disc is compressing a nerve root or an area of the cervical spinal cord. The procedure is done through an approach to the underside of the neck. This allows the surgeon to access the ventral or underside of the cervical vetebral bodies. In the neck, a ventral (underside) approach is favoured (a ‘ventral slot’) and a window is drilled through the vertebral bodies. For the thoracolumbar spine, the most common procedure is a hemilaminectomy, where entry into the vertebral canal is made from the side, directly above the disc space and the vertebral foramen.

Gingi McLeod Age: 8 years Breed: Rottweiler Sex: F/S

At 7 months of age, Gingi was adopted by the McLeod’s from a local shelter and had been an otherwise healthy house pet. Around 11 months ago, Gingi would intermittently cry out in pain after performing certain activities, such as climbing stairs or getting into or out of the car. Gingi also started exhibiting signs of ataxia and rear limb weakness as her signs progressed.

Gingi was referred to Bush Veterinary Neurology Service where an MRI was performed. The results of the MRI showed Gingi had a condition termed Wobbler’s Disease, which resulted in cervical disc protrusions at C4-5 and C5-6. Gingi underwent a surgery called a ventral slot at C5-6 with a fenestration at C4-5. Following surgery, Gingi was sent home on strict bed rest. The McLeod’s were to perform passive range of motion exercises on all 4 limbs and to assist her into a standing position and to go outside with the aid of a help em up harness or sling a few times daily. In her initial post-op period Gingi was not able to urinate on her own and was given medication to help with bladder expression. Gingi also received hyperbaric oxygen treatments several times in the month following her surgery.

Gingi presented to Skylos Sports Medicine to start rehab therapy within a few weeks of surgery. At this time Gingi was too weak to support herself in a standing position, but would move all 4 legs in an attempt to walk with assistance. Her owners were performing passive range of motion exercises 2-4 times daily and assisting her to stand for short periods of time. They felt Gingi had some awareness of her bladder and rectum as she would often vocalize when she had to urinate or defecate. Gingi mainly lied on her side, but was able to get herself into a sternal position if she was lying on her left side. She was unable to accomplish this on her right side. She had anal tone and was able to wag her tail. Gingi had delayed withdrawal reflexes in all 4 legs, but was able to move her legs if persuaded with treats.

At Gingi’s first rehab session we spent time getting to know her and assess what would be good ways to assist her recovery that worked with her personality and with what her owners could accomplish at home as well. Therapy for her first session included; massage and manual techniques, non-thermal class IV laser and specific exercises to promote leg movement and proprioception. One such exercise involved assisting Gingi to drape her body up and over an exercise peanut and rolling her back and forth so both her front paws and rear paws would touch the floor. This is a good exercise to promote proprioception as well as support her body while stabilizing muscles engage.

The McLeod’s were sent home with various exercises, bodywork instructions, and ongoing care parameters. It required daily dedication on her owners part to provide passive range of motion, sensory work such as brushing her in specific ways and helping her body and limbs re-pattern things like sitting up and the steps it takes to accomplish this. Multiple short sessions of standing and assisted walking were also assigned. In addition, Gingi visited Skylos for rehab twice weekly.

Week 1: Gingi had made a few small improvements. Her withdrawal reflexes were stronger in all 4 limbs, she was able to remain sternal on her right side for a few moments and she attempted to stand for a bully stick. However, Gingi was too weak to support her weight by herself when trying to stand. Therapies included; massage, laser and exercises to promote leg movement, balance and proprioception.

Week 2: Gingi continued to make improvements. When taken outside, she was able to stand for a few moments and walked a small distance with little assistance. At this time, her rear legs had more strength and when she tired, Gingi tended to collapse on her front legs. As Gingi would tire rather quickly, we would exercise for a small period of time and then rest. During the second session of the week, Gingi was able to remain in a sternal position on her right side without assistance. Gingi was now also being treated for a UTI. Once a negative urine culture was obtained, the plan was to start Gingi in the underwater treadmill. Therapies included; massage, laser and exercises to promote leg movement, strength, balance and proprioception. The McLeod’s continued a lot of home exercises and mainly concentrated an assisted standing and walking.

Week 3: I was really impressed with Gingi’s improvements. The owners were doing a wonderful job with her home exercises. Gingi was able to walk around with little assistance for around one minute before she tired and tended to collapse. She was also able to stand on her own with little assistance for 30-45 seconds. Gingi was strong enough to walk over 2 inch cavaletti rails for 3 passes. Therapies included; massage, laser and exercises to promote strength, balance and proprioception. Gingi’s urine culture came back negative, so for her second session of the week, she tried the underwater treadmill. Gingi walked for a total of 6 minutes with rests every 2 minutes. She would occasionally knuckle on the left front leg, but overall, did very well.

Week 4: Gingi continued to gain strength at home and was now strong enough to potty on her own outside and no longer needed assistance with bladder expression. Another step in a positive direction that Gingi made at this time was that she was now able to stand on her own from a sit or down position with little to no assistance. She still tired rather quickly, so we would exercise in small increments. Therapies included; massage, laser, underwater treadmill and other exercises to promote strength, balance and proprioception, such as cavaletti rails, figure 8’s and assisted sit to stands.

Week 5: During this week, Gingi had a re-check appointment with the neurologist and she was very happy with Gingi’s progress. During her sessions, Gingi was able to walk around without any assistance and even walked over the 2 inch cavaletti rails on her own. Therapies included; massage, laser, underwater treadmill, assisted sit to stands, cavaletti rails and figure 8’s. Her owners continued to diligently work with her at home.

Weeks 6 and 7: Gingi developed another UTI, so she was not able to go in the underwater treadmill. Her owners felt she was a bit weaker in the rear legs, but overall, was walking well. Gingi had an ataxic gait, but was able to walk around without any assistance. Gingi’s conscious proprioception was slightly delayed, but she was able to “right” all of her paws. Therapies included; massage, laser, sit to stands and started the wobble board and balancing on proprio discs.

Weeks 8 and 9: Gingi continued to do well. She would occasionally knuckle on her left front leg, but this had always appeared to be her weakest leg. This week, Gingi decided she no longer cared for the underwater treadmill and refused to walk in it. During this time, she became able to retrieve treats off of the floor without stumbling or falling. Therapies included; massage, laser and exercises to promote strength, stamina and balance. Her rehab sessions were decreased to once weekly.

Weeks 10 and 11: Gingi continued to recover her strength and was beginning to gain muscle mass. Her gait was less ataxic and she was now able to trot. Gingi’s conscious proprioception continued to improve. Therapies included; massage, laser and exercises to promote strength, stamina and balance. She was doing well her sessions were decreased to every other week.

Gingi comes twice a month for rehab therapy. She is doing well and our work is to continue building on her strength and stamina. Gingi has gained in energy, but still tires after 15 minutes of work. She has been an absolute joy to work with. Gingi has a strong will and was quite determined to walk again. Her owners are also lovely people and were dedicated to her recovery.

Laura Martino-Calfo, RVT,CCRP,CCMP Dr. Faith Lotsikas, CCRT

Skylos Sports Medicine

The ventral slot technique is a procedure that allows the surgeon to reach and decompress the spinal cord and associated nerve roots from a ventral route in veterinary medicine. There are also alternative ways to open the spinal canal from dorsal by performing a hemilaminectomy, but this often gives only limited access. Even when the main pathological changes evolve from the midline, it is necessary to choose a ventral approach.[1]

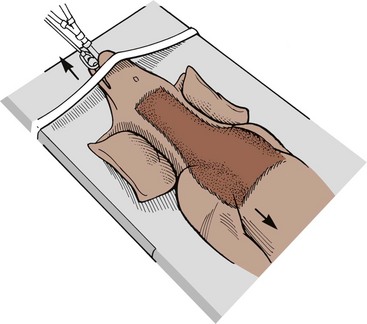

The ventral slot is commonly performed by splitting the ventral soft tissues of the neck, pushing the great vessels laterally and entering the disc space, securing esophagus and trachea which are located in the midline.[2]

Then taking out the medial part of the disc, leaving the lateral part intact and cutting away a small part of the adjacent vertebrae to extend the gap in a vertical manner. By this way a vertical slot including the upper and lower bone plates next to the disc is created.[3]

This makes possible to decompress the spinal cord from the midline and if necessary to both sides including the leaving nerve roots if also compressed.[3]

If necessary a spacer can be placed in the disc space to prevent the operated segment from collapse or secondary kyphosis. Possible serious complications can be complete or incomplete tetraplegia, pneumonia or unnoticed injury of the esophagus.[4]

History[edit]

General data about the discovery and development of the original procedure belong to the British physician Charles Bell who was the first to describe the extent of soft tissue from the ventral into the spinal canal. “It was not until the 1940s that the condition was recognized as a prolapse of the nucleus pulposus.”[5] And it took till 1881 until the first vet, Janson realized a disc extrusion as a classical condition in a dog as the main pathology.

Ventral Slot Technique Meaning

The more detailed descriptions and more precise radiological imaging of the pathologic changes in a dog did not develop until the 1950s. “Hoerlein, Olsson, Hansen, Funquist, and many others contributed significantly to the literature in the 1950s and 1960s, forming the foundations of our current medical and surgical therapies for IVD protrusion”[5] and extrusion. Especial belonging to the surgical technique important advancements in human surgery were made by Robert Robinson, Ralph Cloward[6] and Robert Baily. These basic contributions were taken over to veterinary medicine.[7][8]

Uses[edit]

In veterinary medicine, this is a common procedure to “treat centrally located intervertebral disc herniation”[9]. Veterinary surgeons use the ventral slot technique when the animal shows symptoms of pain and or sensorimotor deficits belonging either to compression of the spinal cord or a single nerve root.

Alternatively, if only a single nerve root is affected it is also possible to release the compressed nerve root via a hemilaminectomy.[9]

Technique and Risks[edit]

This surgery is performed on dogs and cats and a meticulous preparation is needed to prevent any damage on the region of the involved part of the neck and vertebral column. The ventral slot procedure is divided into eight main steps. Because the surgeon isn't allowed not to mobilize or shift the spinal cord - otherwise the affected animal is paralyzed afterwards - for any midline pathology an approach from the ventral direction is mandatory. A vertical skin incision is made from the ventral side in the midline, the ventral musculature is split in the midline, vascular structures are retracted laterally, trachea, and esophagus are mobilized across the midline to the opposite side. Attention is paid on any deep nerve structures as the recurrent laryngeal nerve. The goal is to expose the affected disc and the ventral surface of the adjacent two vertebral bodies. During these steps it is important not to break through the lateral border of the disk space, otherwise the vertebral artery could be damaged.[10]

By entering the disk space and taking out its material a slot is created, following the natural orientation of the disc space itself. This can be expanded into adjacent vertebral bodies by staying in the midline. The extent of the slot should not exceed half of the vertebral body - cranial or caudal, but at the same time is providing more surgical room. Through this slot, disc material can be taken out easily until the disc ligament is reached. By removing this ligament the spinal canal finally is opened. By this step and by taking away bone spurs simultaneously the myelon is decompressed.[2] By now working in a laterally orientation the “foraminotomy” starts. During this part the “osteophyte” is removed in “a 180-degree fashion” and the nerve root is free visible. “The foramen is probed with a nerve hook to ensure that the nerve is free”.[11] To decompress a longer part of the cervical canal a corpectomy is performed from one disc to another, just by the same ventral approach.[11]

Because every surgery comes along with some kind of risk, possible complications are an injury of the structures on the way to the disc space ( like nerves, trachea and esophagus or vessels), resulting in intraoperative blood loss, apoplexy, postoperative paresis or tetraparesis or pneumonia.[12]

Implanted material and effects[edit]

To avoid collapse across the opened disc space several implants are available. Implanted material can consists of “a cervical disc prosthesis”[13], a fixed spacer out of metal (titanium) or synthetic material ( PEEK ). Veterinary medicine is using similar materials as human medicine. Referring to this it is common to insert a cage or allograf. In some cases, the surgeon is using a ventral plate and screws to keep the vertebral bodies together with the implant in position. The main goal of using of a prosthesis is to obtain physiological motion between the two affected vertebral bodies. However, in most cases of myelopathy a secure fusion is attempted. So the compressed myelon will recover after decompression and by time the initial paralysis or sensorimotor deficits will resolve step by step.[13]

Recovery[edit]

Ventral Slot Technique Definition

In general, the animal needs up to 6 weeks for recovery with a normal and positive path of development past surgery if everything goes as planned. During the recovery, statistics have shown that in some cases urinary catheter is needed besides a continuous pain medication. In any doubt of infection especially pneumonia antibiotic therapy should be started early.[14]

Based on actual data dogs receiving physiotherapy which serves the strengthening of the muscles and stimulating the spinal cord functions show a more quickly and better recovery than dogs without such a therapy. [15]

Aftercare and adverse effects[edit]

Ventral Slot Technique Vs

There is a risk of early infection or damage to the operated vertebrae if the animal moves too quick and uncontrolled. Adverse effects like postoperative paresis or tetraparesis or pneumonia appear in some cases. Depending on the width or lateral extension of the slot some dogs may suffer from subluxation of included vertebrae. One can control the early postoperative course by making sure that the animal stays calm and gets controlled, short walks to prevent the overuse of the fixed and still fusing vertebral segment.[16] To ensure a good recovery and good long-term results “serial neurologic evaluation in the postsurgical patient” are recommended according to the data.[1]

Prognosis[edit]

It is hard to foresee the actual outcome on spinal cord injury even with early surgery due to many important facts like animal breed, age, and size. Statistics have shown that dogs ”with cervical spinal trauma have been reported to have a good prognosis (recovery rate of 82%) if the animal does not suffer from pulmonary complications.”[17] In terms of today's statistical basis surgeons are not able to give a secure prognosis about the outcome of the animal.[17]

References[edit]

- ^ abDavis, Emily; Vite, Charles H. (2015-01-01), Silverstein, Deborah C.; Hopper, Kate (eds.), 'Chapter 83 - Spinal Cord Injury', Small Animal Critical Care Medicine (Second Edition), W.B. Saunders, pp. 431–436, ISBN978-1-4557-0306-7, retrieved 2019-12-02

- ^ abVialle, Luiz Roberto; Riew, K. Daniel; Ito, Manabu, eds. (2015). AOSpine Masters Series Volume 3: Cervical Degenerative Conditions. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag. doi:10.1055/b-003-120934. ISBN978-1-62623-050-7.

- ^ abVoss, K.; Montavon, P. M. (2009-01-01), Montavon, P. M.; Voss, K.; Langley-Hobbs, S. J. (eds.), '34 - The spine', Feline Orthopedic Surgery and Musculoskeletal Disease, W.B. Saunders, pp. 407–422, ISBN978-0-7020-2986-8, retrieved 2019-12-13

- ^'Cervical Ventral Slot in Cats - Procedure, Efficacy, Recovery, Prevention, Cost'. WagWalking. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- ^ ab'Intervertebral Disk Disease'. cal.vet.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- ^Cloward, Ralph B. (1958-11-01). 'The Anterior Approach for Removal of Ruptured Cervical Disks'. Journal of Neurosurgery. 15 (6): 602–617. doi:10.3171/jns.1958.15.6.0602. PMID13599052.

- ^'Experimental meningococcus meningitis. C. P. Austrian, bull. Johns Hopkins hosp., Aug., 1918'. The Laryngoscope. 29 (4): 254–255. 1955. doi:10.1288/00005537-191904000-00069. ISSN0023-852X.

- ^Robinson, Robert A. (1959). 'Fusions of the Cervical Spine'. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery. 41 (1): 1–6. doi:10.2106/00004623-195941010-00001. ISSN0021-9355.

- ^ ab'Ventral Slot - an overview ScienceDirect Topics'. www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- ^Glazer, Paul A. (1998). 'SURGICAL APPROACHES TO THE SPINE. Edited by Todd J. Albert, Richard A. Balderston, and Bruce E. Northrup. Illustrations by Philip M. Ashley. Philadelphia, W. B. Saunders, 1997. $125.00, 224 pp'. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery. 80 (4): 611. doi:10.2106/00004623-199804000-00023. ISSN0021-9355.

- ^ abJohnson, Kenneth A. (2014-01-01), Johnson, Kenneth A. (ed.), 'Section 3 - The Vertebral Column', Piermattei's Atlas of Surgical Approaches to the Bones and Joints of the Dog and Cat (Fifth Edition), W.B. Saunders, pp. 47–115, ISBN978-1-4377-1634-4, retrieved 2019-12-02

- ^VOSS, K (2009), 'Preparation for surgery', Feline Orthopedic Surgery and Musculoskeletal Disease, Elsevier, pp. 207–211, doi:10.1016/b978-070202986-8.00029-x, ISBN978-0-7020-2986-8

- ^ abGlazer, Paul A. (1997). 'SURGICAL APPROACHES TO THE SPINE. Edited by Todd J. Albert, Richard A. Balderston, and Bruce E. Northrup. Illustrations by Philip M. Ashley. Philadelphia, W. B. Saunders, 1997. $125.00, 224 pp'. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery. 80 (4): 611. doi:10.2106/00004623-199804000-00023. ISSN0021-9355.

- ^'Cervical Ventral Slot in Dogs - Procedure, Efficacy, Recovery, Prevention, Cost'. WagWalking. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- ^'Discopathie Tierklinik am Kaiserberg'. www.tierklinik-kaiserberg.de. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- ^'Cervical Ventral Slot in Cats - Procedure, Efficacy, Recovery, Prevention, Cost'. WagWalking. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- ^ abDavis, Emily; Vite, Charles H. (2015-01-01), Silverstein, Deborah C.; Hopper, Kate (eds.), 'Chapter 83 - Spinal Cord Injury', Small Animal Critical Care Medicine (Second Edition), W.B. Saunders, pp. 431–436, ISBN978-1-4557-0306-7, retrieved 2019-12-02